City Pastoral

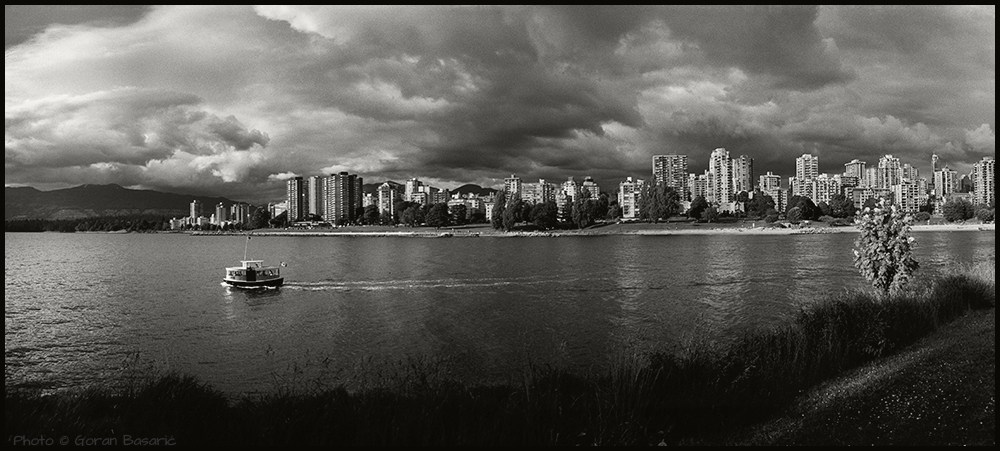

There is a sublime quiet that falls upon a scene like Goran Basaric’s “Ferry Heading Out” a slow roll of beauty that moves through the frame as sturdily and as gently as the small passenger ferry that is put-putting its way west. In the distance, rainclouds loom large over this last long stretch of Vancouver, but no matter. Nothing is going to get in the way of wherever this determined vessel is going. Such an intrepid spirit marks many of the scenes in Basaric’s cinematic-style panoramic photographs included in the collection, “City Pastoral.” But he didn’t start off seeing this way which may be part of Basaric’s advantage for picturing this pacific city the way he does.

Basaric was born in an older version of Belgrade, and came of age as the sun was setting on Tito’s liberal period of independent socialism and Yugoslavia’s political middle way. By the 1990s, market restrictions and ethnic rivalries would break the country but for this moment, youth-struck, Basaric lived in his own creative paradise. He did his degree in Cinematography at Belgrade’s prestigious Faculty of Dramatic Arts under the influence of a new generation of directors dealing more openly with the diminishing stature of their fragile country. Change was picking up speed. There was still inspiration at the center but trouble was crowding the edge of the frame.

In an early series of photographs, Kafana, Basaric put his camera in the thick of his generation’s kafana, or coffeehouse, scene The photographs are shot in dirty blacks and ashtray greys and are lit like an interrogation room in a film-noir movie. In the gloom, cigarettes are waved about like weapons as the students talk darkly of their dreams. The mood of the pictures manages to match the mood in these rooms. Already Basaric was gaining hold of his camera and making his style be part of the story.

Mindful of the documentary photography tradition of the great Magnum photographers, Basaric took to the streets for inspiration. Bresson’s smart-eye strategy for the “decisive moment” when serendipity strikes gold lead him to pan and scan many of Belgrade’s crowded streets but little stood out for him. The light was dull and he felt too closed in by the past. It would take an old camera and a new city to let his talent break free.

All of Basaric’s panoramic photographs in this collection show the full stretch of vision he’s able to achieve with his Horizont camera. Dating to the Soviet Union in the 1960s, the Horizont is an all-metal mechanical swing-lens panoramic camera. It is similar to the Japanese Widelux, but the Horizont, being of Soviet vintage, is a little more capricious in its working. You never know what will turn up in the frame by the time the shot is done. Basaric has come to rely on the built-in unpredictability of the Horizont.

He has used the Horizont to greatest effect in the wide open spaces of his adopted city of Vancouver, an idyllic spot nestled between mountains and water. The panoramic frame commands attention in the same manner as does a stage. Against the draping natural beauty of this setting, fickle actors set out in play. But this is theatre of the ordinary and everyday. Basaric has a sure touch for putting Canadians in their proper place. Just like it took the Swiss-born Robert Frank to make an American look like an American, it takes an expatriate Serbian to let Canadians play by their own rules.

And what of this place he calls City Pastoral? The scenes may be poetic but they’re not soft; there is a lyrical rhythm to Basaric’s photographs that feels very solid and keenly observed. As meditations on the nature of social environments, certainly the term “pastoral” should be taken in stride. These are 21st century urban Canadians going about their business, not country gentlemen lolling about in a Constable painting. Leisure rarely looked less leisurely. In the quick of these passing moments, Basaric captures the peaceable freedom possible in these public spaces. Basaric refers to the “extravagant normalcy” of these scenes and that idea hits the mark. In all these quotidian places, he makes the commonplace appear compelling.

Basaric’s collection has many charms. The formal bride coming up the long sweep of sandy beachstairs is a decidedly west coast version of elegant. The shirtless boys riding the back of the BC Ferry, dumbstruck by sunshine and grandeur. The bicyclist balanced between land and ocean casually needling his way through the surf. Everyone rises a little above themselves to meet the challenge of these monumental spaces. And then slipping in among all the long shadows is Basaric himself. The lucky participant who by chance and determination put himself in the right place at the right time.

Barry Dumka – www.bcreativeconsulting.ca

Artist Statement

I knew little about Vancouver when I first moved to the city in 1994 but it was the change in light that amazed me most. Northern coastal light, especially when lacking in industrial pollution, appears more expansive and purer. Light always leads the way in how I see a place. My training and experience as a cinematographer using light to tell a story still matters when I’m out in open space. It sharpens my senses and pulls me through a scene. Once the light is properly measured, the stage is set to tell a more luminous story.

So the clarity of Vancouver light sparked me to pay closer attention to how people live here. There’s an extravagant normalcy to Vancouver and the northwest region. The widely available luxury of the city’s geographic beauty, and the immensity of its public spaces, allows people to still have a private experience while outside. On this large stage, they allow themselves a casual theatricality. To my eyes, that experience felt different than I’ve seen elsewhere.

For City Pastoral I wanted to capture that interplay between the private and public witnessed in these arcadian settings. To see how the ordinary is made majestic. I believe the place deserves a big voice.